Interests

- Evolution of mating systems and phenotypically plastic traits

- Evolution and maintenance of conditional reproductive tactics

- Causes and consequences of geographic variation in behavior

- Implications of ancestral plasticity

- Behavioral ecology

- Gasterosteid (stickleback) behavior

For undergraduate and graduate students interested in programs related to Animal Behavior, check out the ABS Guide to Programs in Animal Behavior

Research

Study Species

There are a number of stickleback species (Family: Gasterosteidae), many named for their number of dorsal spines (threespine, fourspine, ninespine, fifteenspine!). I’ve spent the last few years working with threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus L.) in British Columbia and Alaska, specifically studying population differences in reproductive behavior. Marine populations of threespines invaded freshwater environments in the holarctic region during the last glacial recession between 15,000 and 10,000 years ago. Depending on the type of aquatic habitat invaded, populations have come to differ in morphology and behavior. This is especially interesting because, not only does it tell us much about how environment affects morphology and behavior but, since the ancestral (marine) populations have changed little in the last 20,000 years, we can determine the directionality of behavior and morphological changes in the more derived, freshwater populations. What is especially interesting about these fish is that they have a very active social life. Male threespines build nests on the substrate and develop a nuptial coloration to attract females and signal territoriality to other males. When males spot a gravid female, they often perform a courtship dance and if the female is interested, she will enter the nest and leave a clutch of eggs for the male to fertilize. The male may do this dance until he collects clutches from several females. He then provides all parental care for the eggs, fanning oxygen over the eggs with his fins as they develop. Males in some populations are very territorial and actively defend their nests and fry from intruders.

Ancestral Plasticity and Conspicuous Courtship Behaviour

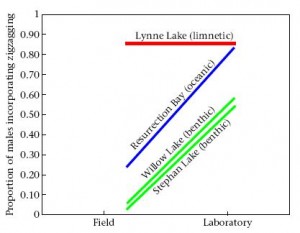

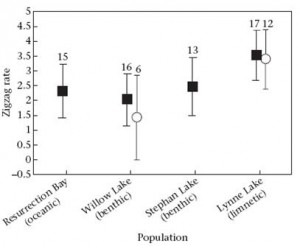

Conspicuousness of courtship depends on potential threats to the nest in some populations. If large foraging groups of stickleback Reaction norm of courtship intensity under field and laboratory conditions.are present in a population they may cannibalize the young in nests they encounter. Males in cannibalistic populations often utilize a less conspicuous courtship display and perform behaviors (diversionary displays) to distract groups away from a territory containing a nest and young. Comparisons of courtship intensity in populations with varying levels of cannibalism have shown that some populations are more plastic in their behavioral response than others. Males from populations in which some degree of cannibalism is present (anadromous and benthic) show an increase in courtship intensity when observed under laboratory conditions (where the threat of cannibalism is absent) as compared to observations under field conditions (where individuals experience foraging groups).

Ancestral Plasticity and Alternative Mating Tactics

My current research focuses on alternative male mating tactics — behaviors males use to obtain matings instead of (or in addition to) nesting and courtship behavior (See Oliveira et al. 2008 for review and synthesis regarding ARTs). Drab colored male threespines have been observed to sneak along the substrate, hiding behind objects and in vegetation, and attempt to rush into nests of courting males in order to fertilize eggs that are not their own. There are several factors proposed to elicit sneaking in individual males but of greater interest is the fact that there are some populations in the Pacific Sneaker male near shore at Big Lake, AlaskaNorthwest where sneaking occurs at high frequencies (Alaska) and other populations where sneaking has never been observed (British Columbia). Freshwater populations in this region are all derived from marine ancestors so it is plausible that ancestral plasticity in this behavior has influenced geographic variation in the propensity to sneak. There may be certain characteristics (genetic and/or environmental) specific to populations in which sneaking is absent. My current work involves:

Regional investigations of the conditional factors suggested to covary with sneaking behavior (sex ratio; inter-nest distances, visibility, etc.) Are any of these factors correlated with an in situ propensity to sneak both within and between regions (Alaska vs British Columbia)? Intra- and Interspecific comparisons of sneaker color variation and investigation of the adaptive significance of sneaking patterning. Is there low variability in sneaker coloration across populations? Are sneaking males utilizing crypsis or female mimicry? Laboratory-based comparisons of sneaking propensity with lab-reared individuals from sneaking and non-sneaking populations. Is there a genetic component underlying variation in sneaking propensity? Utilizing population and regional comparisons will allow me to understand:(1) the extent of genetic variation underlying the sneaking phenotype, (2) factors that elicit sneaking, and (3) the role of the ancestral state in influencing the regional pattern of sneaking behavior.

Other Research Projects

Fourspine Stickleback

Fourspine stickleback (Apeltes quadracus) are a marine species of stickleback that breed in vegetated, brackish waters. Their distribution ranges the eastern shoreline of North America from North Carolina to the St. Lawrence River. In areas where eelgrass and other estuarine plant species are becoming increasingly sparse, sightings of fourspines are progressively spotty, as they depend on vegetation for nestbuilding.

My interests in fourspines pertain to their mating behavior. Fourspines have been observed to utilize sneaking behavior to steal fertilizations. Along with several other stickleback species known to exhibit this behavior, it would be an interesting comparative analysis to examine tactic frequency, plasticity, coloration, and functionality of sneaking behavior across several groups of stickleback. My goal during the spring/summer 2007 was to collect wildcaught fourspines and induce sneaking behavior under laboratory conditions to determine the plausibility of conducting a comparison. Even with locality data obtained from the CT and MA DEP, it turned out to be extremely difficult to find fourspine breeding sites. After an entire summer of daily collection effort, only five potential sites were found and, of these, only two or three were amenable to frequent collection attempts. While fourspines maintained in the lab were healthy and of reproductive age, they were past breeding condition by the time they were collected. It is my goal to attempt these live collections again in the future to run behavioral trials similar to those I am conducting on threespines. Given the difficulty involved in finding fourspine breeding sites, it behooves me to increase collection effort at other sites, in the future, to determine whether fourspines are still present at some of the sites they were historically observed. According to homeowners in several areas, the aquatic vegetation along the shore has decreased drastically over the past decade. It would be especially interesting to continue monitoring the abundance of breeding individuals at the sites that are easily accessible.

Future Research Prospects

I hope to gain insight into both the external and internal factors that foster or limit the evolution of alternative mating tactics. Once the interplay between ancestral plasticity and the environmental contexts eliciting sneaking are understood, my long term goals are to evaluate hormonal correlates of sneaking behavior, and, ideally, transcriptional profiles of the brains of sneaking and non-sneaking males to understand the genetic and physiological underpinnings of sneaking behavior. Such research should be attainable given the availability of the genome sequence and genomic tools developed for this model system.

Publications

Foster, S.A., K.A. Shaw, K.L. Robert, J. A. Baker. 2008. Benthic, limnetic and oceanic threespine stickleback: Profiles of reproductive behavior. Behaviour 145 (4): 485 – 508. PDF

Shaw, K.A., M.L. Scotti, S.A. Foster. 2007. Ancestral plasticity and the evolutionary diversification of courtship behaviour in threespine sticklebacks. Animal Behaviour 73: 415 – 422. PDF

Field Blog

Here’s my FIELD BLOG — includes updates and pictures (a work in progress)…BC and AK field season now DONE (still behind on blog entries, however…)

Education

B.A.(2004) Clark University, Department of Biology

M.A. (2005) Clark University, Department of Biology

Doctoral Student (2005 – Present) University of Connecticut, Ecology & Evolutionary Biology

Contact Info

Katherine Shaw

Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

75 North Eagleville Rd, U-43

Storrs, CT 06269

_______________________________________________

Office: TLS 363

Voice: (860) 486-4638

Fax: (860) 486-6364

Email: katherine.shaw@uconn.edu